Should you learn to program a robot if you’re never going to program a robot?

If you value STEM education, the quick answer is yes because maybe soon you will need to program a robot, or a machine of some kind, or do something comparable in nature to programming, because the world is becoming more and more technologized. Jobs leverage complex interfaces; common tasks require machines used in a programmatic way.

A second, related, and maybe more useful answer is that learning how to interface with the world in a logical, coherent, explicitly definable way is not only important but increasingly acts as a dividing line between quality of education, and between qualities of lifestyle. Those who have learned to engage their environments with careful reasoning are more likely to get along in life (on average), and those who haven’t, won’t (on average) — and it is much harder to learn this skill later on in life. That that these same skills may increase in probability of being employed, literally, in “the jobs of the future” acts a side point.

STEM is of course more than just T and T is of course more than just programming, and we shouldn’t ever forget that a lever is technology or that a piece of steel is engineering, or that understanding the how and why of biochemistry is as important as understanding how your printer works. But S and T and E and M all work together, and T (or E with a focus on T) takes the most visible place in many people’s view. It’s right there in front all the time.

So, yay STEM! Children should know how the world works and be able to engage their world effectively and at an intuitive level by the time they reach adulthood.

* * *

But there’s a problem. At least, I think it’s a problem. You can tell me I’m being ridiculous and regressive, and you wouldn’t be the first.

The problem I seem to identify is that STEM increasingly is viewed as the principle and superlative way of not only interacting with but also understanding the world.

…so what’s wrong with that?

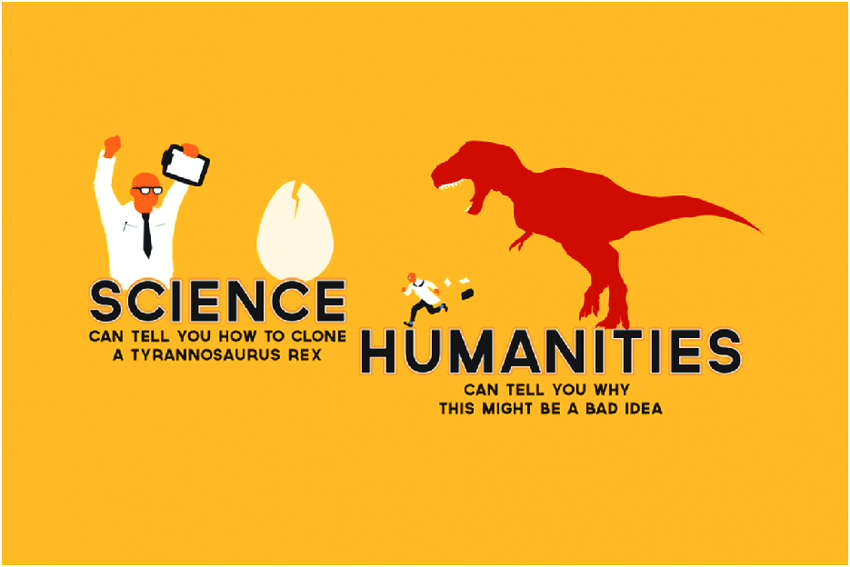

(Credit https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Elizabeth-Stephens/publication/347895625/figure/fig1/AS:981593355214848@1611041501611/Poster-for-college-of-humanities-at-the-university-of-Utah-2015-Science-can-tell-you.png)

Now, back in my late teens, when (coming from a more humanities-oriented background) I was engaging in STEM (not by that name) and loving it, I was a little irked by this image above. Many others have felt this way as well, or still feel this way. I didn’t strictly disagree with the message that answering broader questions is important, but I had some nebulous feeling that with proper attention to the how, the why would sort of…solve itself. Or, to give my teenage self more complete credit for thinking through my opinions, I reasoned at the time that the humanities’ fundamental lack of firm objective reasoning (since, necessarily, the liberal arts require a comparative analysis to function) impeded it from the kind of sound judgement that only critical assessment of facts could achieve.

At one level, this is clearly true. We appeal to liberal arts, the humanities, when we want to understand the abstractions of life, the art, the culture, the language, the ethos of something. We appeal to the sciences when we want to understand its mechanisms and the natural outcomes of those mechanisms. Surely this resolves our dinosaur outcome dilemma? Jurassic Park would have no problem if the logical process were to be carried through to conclusion ahead of time and proper security precautions implemented.

Ok, true — but what about the question of benefit to humanity? Let’s forget about the danger and imagine that we solve every possible technical hurdle so a dinosaur is no more dangerous than a roller coaster (still potentially dangerous, but well under control). We’re not asking the question now of what could go wrong but rather what are the implications? Is that a technical question or is that a humanities question?

Really, it is a philosophical question, which means it’s both.

Soft-sounding philosophical conclusions have a tantalizing way of popping out unexpectedly from hard-nosed scientific discussion. Freud and Jung are wonderful primordial examples of this. We may view some of their views as outdated, but there are newer examples too — Asimov for one, and Church and others, and even more recently Richard Dawkins and Neil deGrasse Tyson both touch on it in very different ways, and there are more extreme examples to be found in the likes of Jeremy Narby, and the list goes on, just do some searching, it’s a fascinating thread! — and so the gradient from hard science to free-floating philosophy proves challengingly narrow. This is as it should be, for the humanities and the sciences are only after all different questions on the same topics and ultimately subject to the same overarching conclusions — but I’m getting ahead of myself. I’m supposed to be contrasting the question of science answering a question with that of humanities answering that same question.

So back to the original thought, for a while: We’ve eliminated the dangers wrought by a poorly managed Jurassic Park, and are now questioning what we get out of it, and what that means, and whether it’s worth it. In the meanwhile the doers in life may move ahead without asking our opinions on the subject and unlock the gates to the park, but the movers and shapers from the humanities department still have leverage to steer — in journalism, in publishing, in podcasting, and in speaking, in blogging, in teaching, and even in lobbying. This discourse may come almost universally at the tail end of the spectacle, but it retains a measure of control after the fact, enough sometimes to clean up the mess (or make a worse one, but that’s another issue).

So we can and maybe must look to humanities to answer these questions, because how else can they be answered? In this way we stumble over the trick of the scientifically objective: it can make no value judgements, not and hope to keep any merit at all as a science. Even the most deeply insightful, opinionated science can only posit a framework of conclusions which the positor may hope will lead the observer toward an ideally inescapable action — but it can’t decide. It can’t opine.

That lack of decision of science is all to its benefit, and as another side note many issues this last decade or so in scientific research have come from its curators’ attempts to cross this line, sacrosanct for very good reason. The smallest iota of opinion in a science is enough to destroy it. The mixed substances of observation and valuation render together a subtle poison, that worsens the longer it sits, and which dark genie is hard to cram back in its bottle*.

So if science can’t — and shouldn’t — answer an “ought we?” question, this leaves humanities as the answerer.

For all this kind of question we have only humanities to look to, and when we weaken its leverage by calling it less than it is, by underestimating it, as I so easily did in the past, we weaken our ability to answer this important category of question usefully. (Another side note: humanities has problems too, an obvious observation, which I intentionally am eliding in this discussion).

Likewise if we then weaken by lack of attention or outright dismissal our children’s abilities to dialogue successfully in this medium, they never gain the ability to qualitatively answer these kinds of questions in their own life — and, in my possibly biased opinion, it is why so many highly intelligent people become so easily brainwashed; call something a fact and it can be your new master, if you fail to question it, too (“opinions dressed up as facts”).

This potential gap in thought process skills is why STEM isn’t the be all and end all of education. This is why we need to accept as students the interminable, boring, seemingly irrelevant analyses of classic novels, or learning how to read and write poetry, or reading how some country or other came to be the way it is.

How can you decide what to do next with any measure of aptness if you don’t know what came before, or how A causes B? We wouldn’t stand for such namby-pamby in STEM, so we shouldn’t stand for that in humanities, either. That boring history, that pointless textual analysis becomes a kind of keen insight into the human (or cosmological, or even metaphysical or spiritual) side of the story, where good judgement starts — just after good science ends.

And here, back on the point we got ahead with earlier, is that same arrival of the philosophical: Science implies the origins and meanings of philosophical; without its rigor, without its indications of direction and relationships, philosophy is no more than a fevered dream, an abstract landscape without framework. Humanities allow discourse, discussion, decision. Without it philosophy languishes in the fight pits of scrabbling empiricists. Only the fluid subjectivity of humanities brings the breath of freedom and understanding to the contextless world of science.

I realize this last paragraph, if anyone were to read it, would likely lead quickly to antagonism from some, and skepticism from more. I can answer only: the more you read, of all things, the more sense it makes, if you’ll let your mind be observant, and find the latent associations. At least, that’s how I see it.

道

* Not to say that science must eternally be purely observation, as hypothesis and conclusion naturally follow. But conclusion is not value judgement. One may follow the other quickly and easily, but that jump, however slight, crosses a chasm.

(M.m)